Chapter Two – The Way

C.S. Lewis begins The Abolition of Man by pointing out that we do not pay close enough attention to elementary textbooks. This is problematic because some authors may unintentionally smuggle into lessons certain ideas about morality that will lead children down the path of death and destruction. Such is the case with “The Green Book” in Lewis’ possession, an elementary English textbook meant for “boys and girls in the upper forms of schools.”

The authors of The Green Book advocate for the notion that there is no objective standard by which to judge whether a thing is either pretty or sublime. They say that such words represent only our feelings about something, while saying nothing true or false about the world around us. That is to say, human beings cannot have any meaningful or value-laden contact with reality.

In a post I published three weeks ago, I explained that Lewis believes that such a doctrine—which he calls subjectivism—will lead to “Men without Chests,” the title of chapter one in The Abolition of Man.

In this post I will explain Lewis’ arguments against subjectivism using chapter two— which he titles, “The Way”—and Dr. Arnn’s lecture by the same title in the course “An Introduction to C.S. Lewis: Writings and Significance.”

The Way

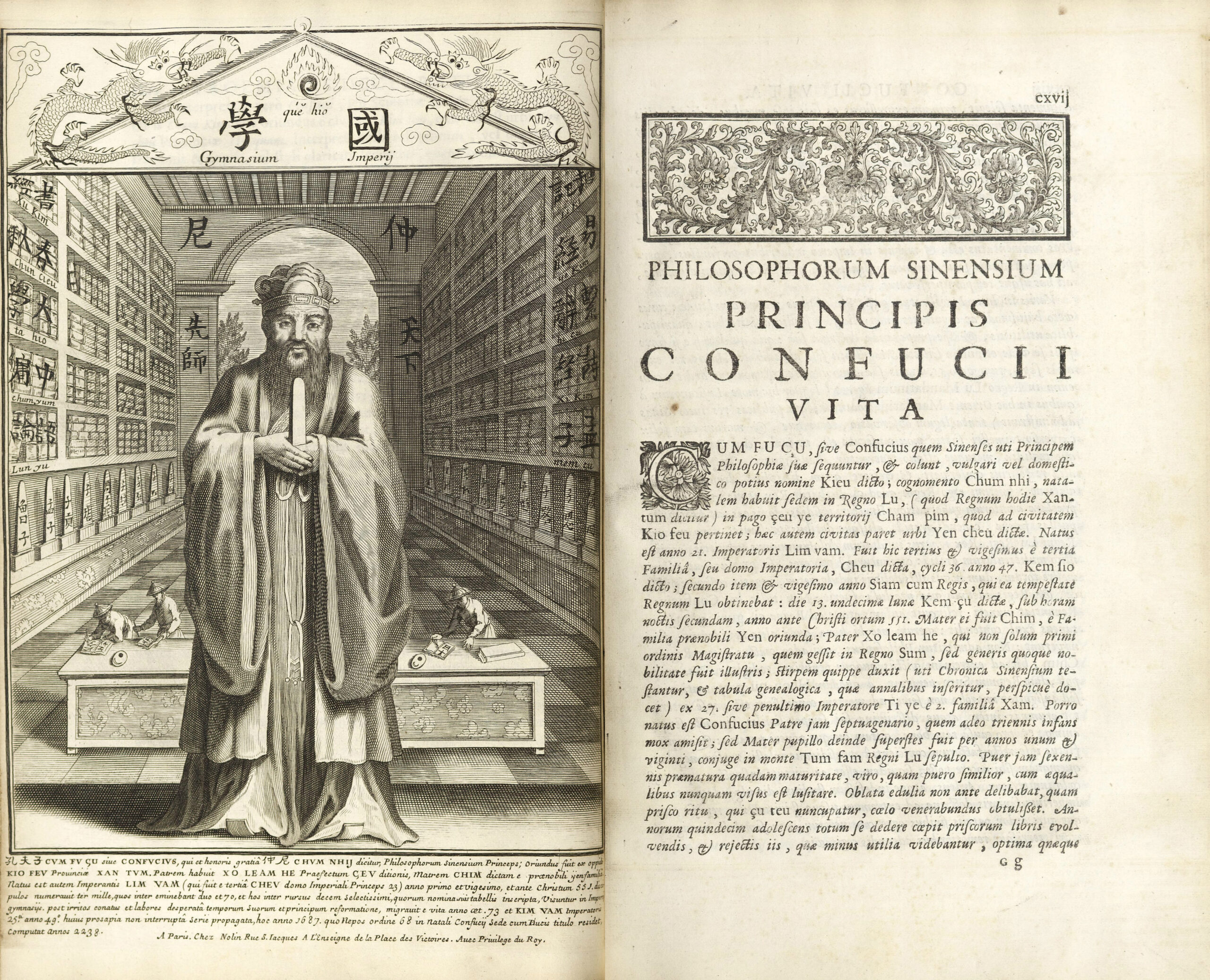

Dr. Arnn begins by explaining that the “second chapter is called ‘The Way,’ in the sense of the way to go, the natural law, first principles, the Tao, [Lewis] says, after the Chinese word for ‘the way.’” Lewis explains that,

The Chinese also speak of a great thing (the greatest thing) called the Tao. . . . It is Nature, it is the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time. It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar.

Lewis further explains that the Tao or The Way is “the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others are really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are.”

In other words, nature provides objective standards around which we ought to orient our lives. The fact that we use a single name for things of which there are many (e.g., an oak tree or a human being) shows that there is a “way-of-being” proper to each thing, and that we can recognize these ways-of-being.

We don’t say that the end of an acorn and the end of a baby are the same simply because they both eventually die. There is a certain point at which we can look at an oak tree and admire an excellent one, and the same is true of an excellent human being. To ignore this fact—that a man is a unique thing with a unique nature—is to abuse man and violate his proper way of being.

Contradictions in The Green Book

However much the authors of The Green Book accept subjectivism regarding some values, they must admit that they themselves accept objective values as well. The very act of writing their book demonstrates that they aim to produce “certain states of mind in the rising generation, if not because they think those states of mind intrinsically just or good, yet certainly because they think them to be the means to some state of society which they regard as desirable.”

What their particular end is, is not important. The mere fact that they have an end is important. This end, to instill in the rising generation a rejection of objective values, “must have real value in their eyes” or else they would not have written the book. The authors are therefore caught in a contradiction.

Lewis explains that,

This thing which I have called for convenience the Tao, and which others may call Natural Law or Traditional Morality or the First Principles of Practical Reason or the First Platitudes, is not one among a series of possible systems of value. It is the sole source of all value judgements. If it is rejected, all value is rejected. If any value is retained, it is retained. The effort to refute it and raise a new system of value in its place is self-contradictory. There never has been, and never will be, a radically new judgement of value in the history of the world.

The reason this is so, is because if one argues that there is a way that things ought to be, which the authors of The Green Book argue, then they are necessarily accepting the legitimacy of the Tao.

Lewis argues there may be advances in the Tao, but not innovations. For example, the Christian precept, “Do unto others as you would have done unto you,” is an advance on the Confucian precept, “Do not do unto others as you would not have done to you.” However, the Nietzschean ethic is an innovation because he throws out the Tao and provides completely new values.

Lewis gives the analogy that the former is like saying, “You like your vegetables moderately fresh; why not grow your own and have them perfectly fresh?” Whereas the latter (Nietzschean ethic) is like saying, “Throw away that loaf and try eating bricks and centipedes instead.” Hence, attempting to scrap the Tao while remaining in the Tao (what the authors of The Green Book do) or attempting to scrap the Tao and provide a completely new set of values (what Nietzsche does) both lead to the abolition of man.