DEEP DIVE: Understanding the Laffer Curve

It all started with a napkin.

In our recently released course, “Supply-Side Economics and American Prosperity with Arthur Laffer,” Dr. Laffer and Dr. Brian Domitrovic recount the origin story for the now famous “Laffer curve,” an image that has become synonymous with supply-side economics. You can view a sneak peek of the episode below:

As our students have begun taking the course, we’ve noticed that several of the most commonly missed quiz questions came from “Lecture 2: The Laffer Curve.” So we thought we’d take some time today for a deeper dive into how it works.

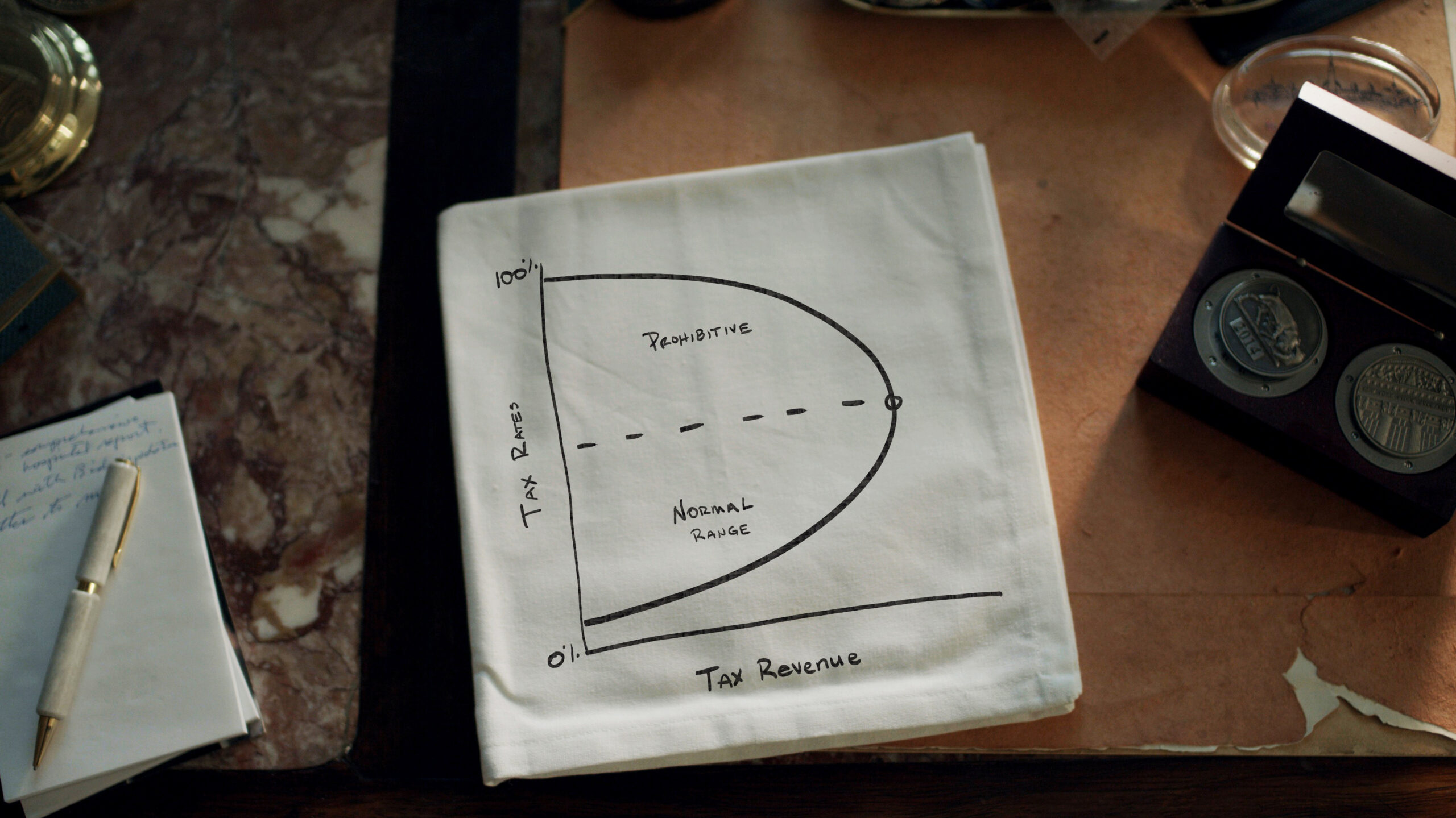

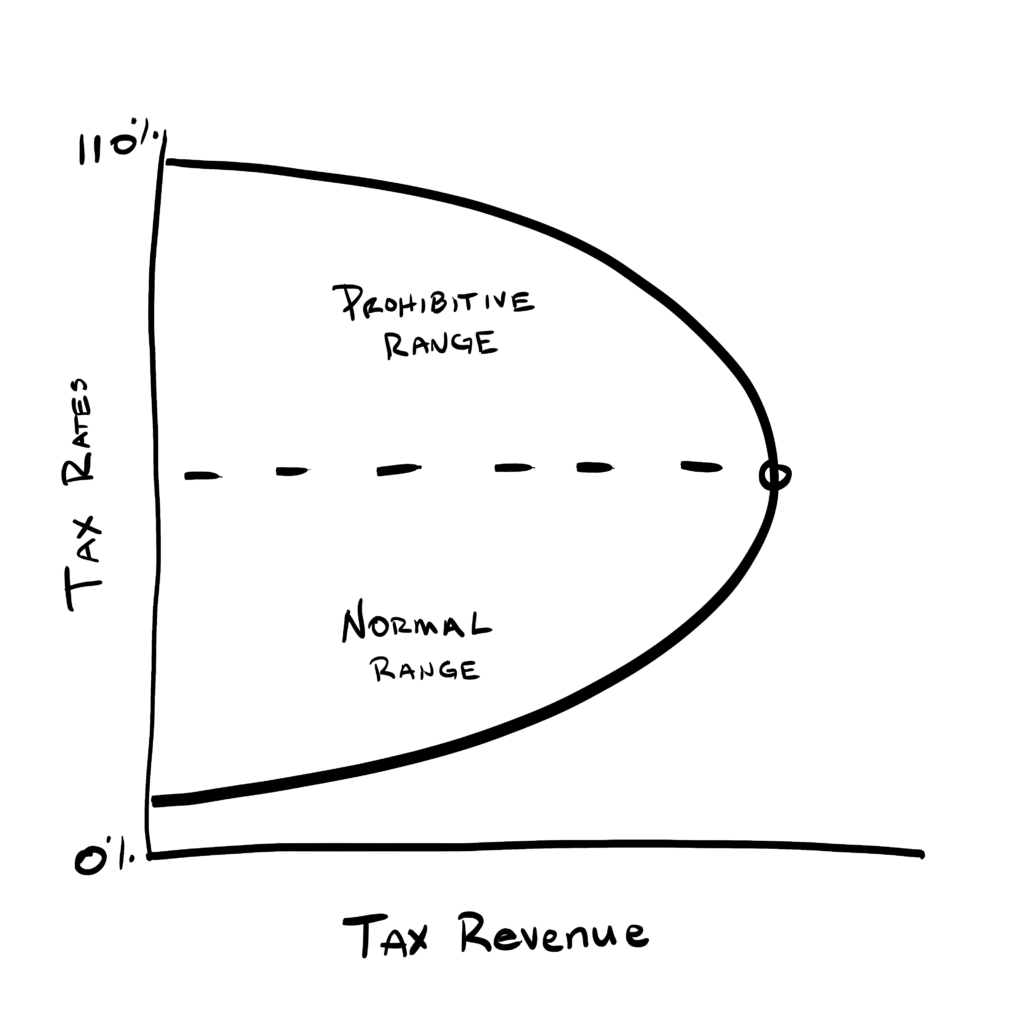

The Napkin Sketch

Dr. Laffer sketched the Laffer curve on a napkin for Donald Rumsfeld, then Chief of Staff to

President Gerald Ford, to explain why a tax increase of five percent would not result in a five

percent increase in revenue from taxes. It first entered the public square through Jude Wanniski’s article, “Taxes, Revenues, and the ‘Laffer Curve,’” in the Winter 1978 issue of The Public Interest, before becoming a cultural phenomenon in the 1980s.

According to Dr. Laffer, the Laffer curve is simply a representation of principles that have been understood by economic thinkers for thousands of years—from Adam Smith to Ibn Khaldun to John Maynard Keynes. The problem, and the opportunity for Dr. Laffer’s own contribution, was that these principles haven’t been applied consistently by economists, especially in the 20th century.

The Effects of Pricing

A simple way to understand the concept is to think about how a shopkeeper prices products in his store. If a product is priced too low, customers might enjoy the discount, but sales of the product will generate a loss for him. However, if a product is priced too high, no customer will want to purchase it, so it will also generate a loss for the shopkeeper as it collects dust on the shelf. The optimal price is somewhere between these two extremes. Customers will want to believe that the price they pay for it is fair for the value of the product. The shopkeeper will want to cover the wholesale cost of the product while additionally making some revenue to keep for himself.

This same principle applies to taxation. If taxes are too low, government will not generate enough revenue to operate its essential functions. If taxes are too high, no one will want to work. Or, they will seek ways—both legal and illegal—to reduce their reported taxable income.

Tax Rates and Government Revenue

Dr. Laffer explains that tax rates have two effects on government revenue. First, higher tax rates increase the revenue per dollar of tax base. This is called the “arithmetic effect.” If the tax rate is 25%, for example, government takes $0.25 in tax revenue for every $1.00 a person reports as income. If the tax rate rises to 50%, government takes $0.50 in tax revenue for every $1.00.

Second, higher tax rates reduce the incentive to work. This is called the “economic effect.” If a person works 40 hours per week making $10/hour, he will make $400/week in pre-tax income. If the tax rate is 25%, his take-home pay that week will be $300. But if the tax rate is 50%, his take-home pay will only be $200.

Let’s say he’s given the opportunity to work an extra 10 hours that week at the same $10/hour. At a 25% tax rate, this is $75 in take-home pay. At a 50% tax rate, this is only $50 in take-home pay. Is an extra $50 worth working 10 additional hours? This personal choice depends on the individual worker, but the higher the tax rate rises, the less inclined he will be to work the extra shift. The monetary return on his investment of time will continue to proportionally decrease every time the tax rate goes up.

Taxation and the Laffer Curve

To state it plainly, contrary to the opinions of many economists and politicians today, increasing the tax rate does not automatically guarantee increased revenue for the government. Keynesians assume that worker output and production are given. This would mean that simply raising the tax rate would increase tax revenue proportionally. Dr. Laffer instead believes that output and production respond to government policies.

Why? Because everyone in a marketplace responds to incentives. Just as a customer won’t buy a given product on the shopkeeper’s shelf if he believes that product is priced above its value to him, workers in the economy won’t want to work if they believe the after-tax income (i.e., their paychecks after taxes have been deducted) they receive for their work isn’t fair value. Or they’ll find tax loopholes and other means to shelter their income. Or they’ll lie to the government about it, in order to keep more of it in their pockets.

The Logic of the Laffer Curve

Following the logic of the Laffer curve, then, raising tax rates will do three things:

- It will increase the revenue raised by government per dollar of tax base. For each dollar of reported income taxes, government will receive a greater share.

- It will disincentivize production. People won’t want to work more if government takes more and more of their paycheck from them.

- It will shrink the tax base as more people look for ways to evade and avoid paying additional taxes.

Ready to learn more about how understanding the principles of macroeconomics can help unleash American prosperity once again? Enroll today.