Zephaniah Swift on Marriage and Happiness

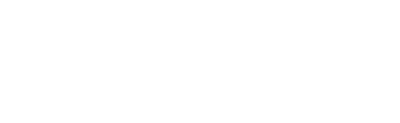

In our new online course, “The Real American Founding: A Conversation,” Dr. Thomas G. West names some of his favorite members of the Founding generation, including a couple that do not have the name recognition of a George Washington, a Thomas Jefferson, or an Alexander Hamilton. One of these underappreciated “second-tier” Founders is Zephaniah Swift, who Dr. West admires most for his thoughtful treatment of marriage in the fifth chapter of his System of Laws for the State of Connecticut, entitled “Of Husband and Wife.”

Swift begins by stating the Founders’ view that marriage is the human relationship which contributes most to human happiness:

The connection between husband and wife, constitutes the most important, and endearing relation, that subsists between individuals of the human race. This union, when founded on a mutual attachment, and the ardor of youthful passions, is productive of the purest joys and tenderest transports, that gladden the heart.

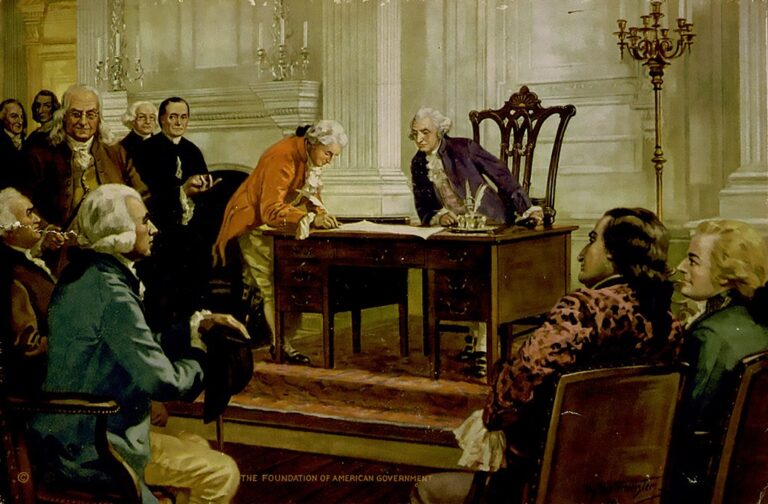

But to achieve such happiness, certain conditions must be met. Most importantly, the spouses must be recognized as equal in dignity and rights. For Swift, dignity demands monogamous marriage. In barbaric countries, past and present, polygamy was common practice. Women were regarded as “slaves” who were “merely objects of lust and sensuality.” By contrast, it is the mark of “civilization and refinement of manners” when women are properly respected:

[S]ociety may be said to have arrived to the highest point of improvement, when the charms of their beauty and the softness of their virtues are united in bestowing the sweetest joys on domestic life, when they are considered as the equal companions and friends of the other sex, and when the intercourse of the sexes is regulated by sentiments of decency, delicacy and propriety.

Marriage as a Civil Contract

Swift argues that the best way to promote marriages of this character is to treat them as civil contracts with mutual responsibilities for the spouses that can be supported by laws. He goes on to describe how to uphold the marriage contract and how to regulate divorce.

The first step in civil marriage is simply agreeing to a contract. Both parties must mutually consent to marriage and agree to abide by certain terms. Similar terms are still expressed today in traditional marriage vows, when a couple promises to love and cherish each other till death. The terms of the contract are essential for helping the law punish one of the parties when they fail to observe their marital duties.

Further, Swift details how and why the engagement should be publicized. The state of Connecticut required marriages to be proclaimed in church or at a public meeting, or posted to a public bulletin board eight days prior to the ceremony. Such a regulation helps to illustrate that this contract, “which is of so much consequence for civil society” should be regarded as “serious, solemn and deliberate.”

Dissolving Marriage

The same seriousness can also be seen in Swift’s account of how marriages can be dissolved. Before the advent of Christianity, when women were treated as mere “slaves,” husbands had the “power of divorcing them at pleasure.” According to Swift, even with the improvements of the “Grecian and Roman States, divorces were admitted on the most trifling pretenses.”

Such a policy would threaten the integrity of marriage and the happiness that can be found in marriage. However, Swift also thought that divorce must be available for marriages that truly fail. The laws governing divorce must strike a balance. Swift summarizes Connecticut’s policy this way:

We neither admit that marriage is indissoluble, so as to involve a person in wretchedness for life, who is unfortunate in forming a matrimonial connection; nor do we allow it to be dissolved upon such slight pretenses, as give the parties the power of releasing themselves from it, when whim, caprice, or a relish for variety shall dictate. Substantial reasons only, which show that the design of marriage is defeated, will have influence, and the validity of these reasons must be judged of by a court of law, and not by the party themselves.

This is the kind of rigorous thought that statesmen like Zephaniah Swift had to engage in to bring the Founders’ principles to life. If we agree that strong marriages will promote human happiness, then we, too, must consider how to achieve the proper conditions for such marriages.