The Legacy of the Spanish-American War

On February 15th, 1898, the USS Maine exploded and sank in Havana Harbor under mysterious circumstances. The incident, along with the sensationalistic reporting of Spain’s ongoing counteroffensive against revolutionaries in Cuba, ignited Congress and the American people into a war frenzy.

Despite President McKinley’s attempts to resolve the conflict peacefully, he yielded to political pressure and signed Congress’s war declaration against Spain on April 20th, 1898. America’s stated objective in the Spanish-American War was simple: bring Spain’s four-hundred-year rule in Cuba to an end. But in one of history’s many ironies, the war began in Manila Bay in the Philippines, nearly 10,000 miles away from Cuba. There, Commodore George Dewey famously sunk the Spanish squadron, and America then sent in the Army to occupy the island of the Philippines.

Over the next few months, American forces proceeded to make quick work of the Spanish Army and Navy in the Pacific and the Caribbean, forcing Spain to sue for peace.

The 1898 Treaty of Paris, however, required Spain to do more than merely relinquish its grip over Cuba; it stipulated that Spain would transfer its colonial possessions of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States. The people inhabiting these territories had no say in the matter, and the United States had no intention of converting these lands into states, nor extending to the inhabitants the rights of citizenship. Instead, America would rule these newly-minted colonies without their consent. The nation that was born out of a revolution against British colonial rule was now an imperial power.

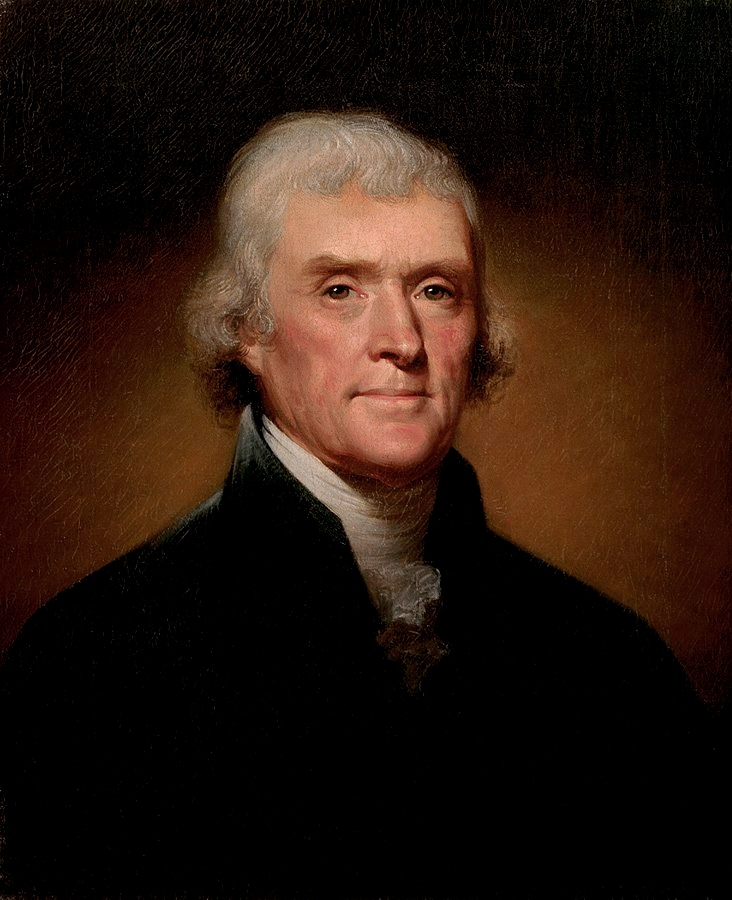

Why did America turn to imperialism? According to Professor Anton, in “American Foreign Policy,” the progressives of the late nineteenth-century had little use for the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that all nations have a right to a “separate and equal station.” In fact, they flat-out rejected that idea. Whereas the Founders believed that all nations have a duty to respect the right of other nations to govern themselves, the progressives believed they possessed both a right and a duty to intervene in those nations they deemed not sufficiently civilized. Professor Anton explains:

Much of what the United States tried to do in these acquired territories, according to progressive doctrine, was to bring them up to American standards of civilization. . . . Bring up their economies, their industries, their societies, and their political practice up to what the people trying to do the work considered to be acceptable modern standards. That is to say, the Progressives looked at these countries paternalistically.

In other words, progressives believed that a nation’s sovereignty was not an inviolable right possessed by all nations, but a conditional right—a right guaranteed only to those nations that had achieved “American standards of civilization.” And this explains why the progressives made the fateful decision at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War to transform the United States into an imperial power.