Were the Founders Isolationists?

The term “isolationist” first appeared in the American political lexicon at the close of the nineteenth century when the United States began to flirt with the idea of acquiring colonies overseas. The pejorative was invented by American imperialists to insult people who opposed expansionist policies. Anyone who advocated a more restrained foreign policy—i.e., the Founders’ foreign policy—was labeled an “isolationist,” meaning both stupid and old-fashioned. And by the late 1930s, the insult was imbued with a much more caustic meaning—“Hitler apologist”—and carried sufficient venom to poison an opponent’s reputation.

In “American Foreign Policy,” Michael Anton explains that “isolationist” is still used today as “a kind of crass playground insult,” which is “flung at people who favor a more restrained policy than the person flinging the insult.” He says that if you want to understand what true isolationism is,

think of Japan from 1603-1868. . . . Japan had no contact with the outside world for over 250 years. In fact, if you simply rowed your boat up to the shores of Japan and went ashore waving and smiling expecting a friendly reception and hoping to meet some Japanese people and soak up a little Japanese culture, as likely as not, you’d be executed, by a samurai sword cutting off your head.

That’s isolationism.

This raises a few questions. If “isolationists” were not arguing for Japan-like isolation, then what in fact were they arguing, and how would they identify themselves?

To begin, the “isolationists” never referred to themselves by that term. They typically referred to themselves as nationalists or noninterventionists. This is how the Founders understood themselves, as Anton explains, drawing upon two famous Founding-era documents—the Declaration of Independence and George Washington’s Farewell Address.

The Declaration of Independence lists the first and highest reasons why government is established: for a people’s “Safety and Happiness.” In order to be happy, the highest end for which government is established, a person must first be alive, which is why safety is listed first. To protect the lives of its citizens is the foremost priority of government. From a foreign policy perspective, safety implies keeping the homeland safe from invasion by a hostile foreign power.

The Declaration also says that governments “are instituted among Men” to “secure these rights,” namely the right to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” Hence, government must not only protect the lives of its citizens, but it must protect their other rights, too. Again, from a foreign policy perspective, this means a government must protect its citizens from being enslaved—which would eradicate citizens’ right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness—by another foreign power.

Furthermore, because “all men are created equal” and government derives its “just powers from the consent of the governed,” no nation has the right to enslave or subjugate another foreign nation. This is the foundation of national sovereignty, which in the eyes of the Founders meant that each nation possesses equal rights as a nation, much like each individual person possesses equal natural rights. Nations are obligated to respect the equal rights of every other nation.

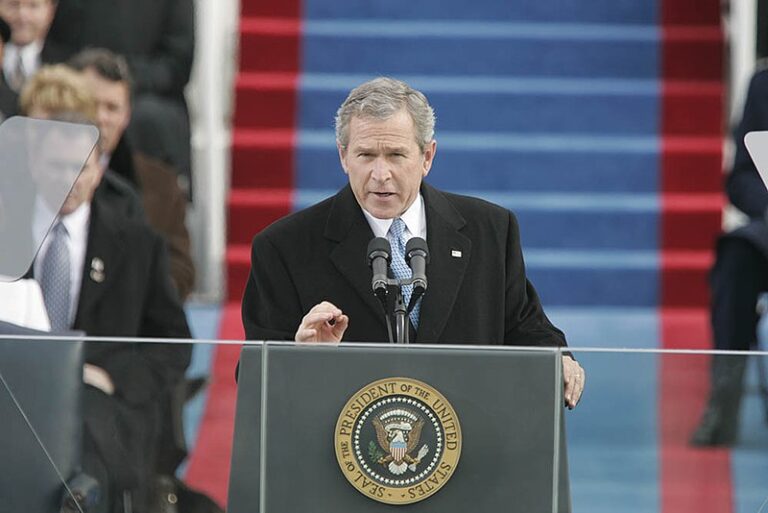

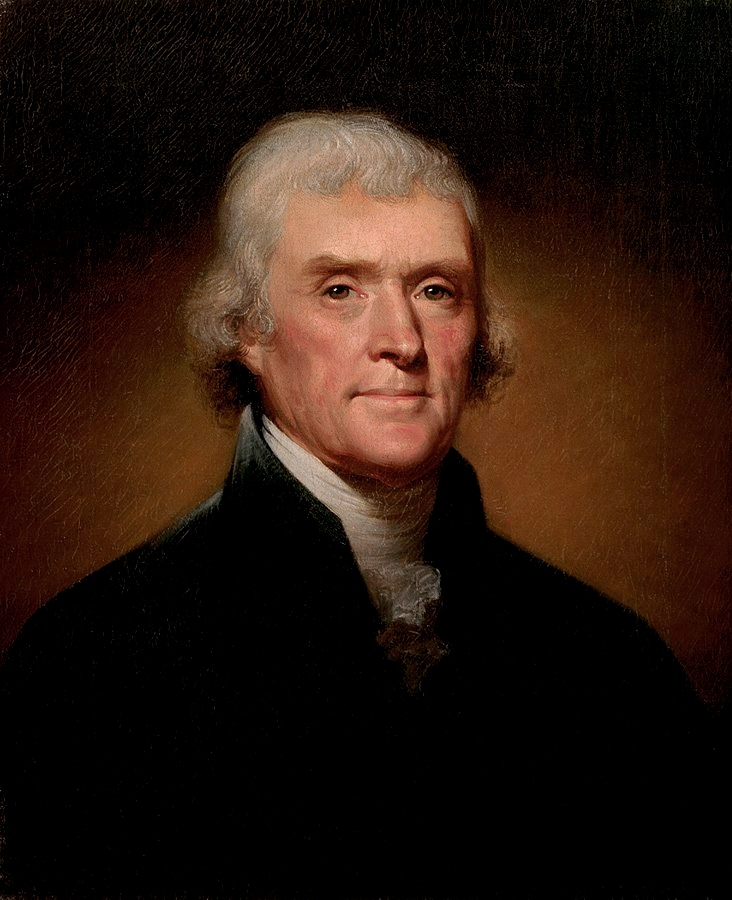

The other document Professor Anton mentions is George Washington’s Farewell Address. Drafted initially by Alexander Hamilton, it was later edited, with minor revisions made by Washington himself. Professor Anton points out that there is a well-known and commonly used phrase that is habitually misattributed to Washington’s Farewell address—”entangling alliances.” That phrase comes from Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address, given in March 1801.

In his First Inaugural, Jefferson explains that he is going to list the “essential principles of our government, and consequently those which ought to shape its administration.” One of the principles that he says should guide us is to have “entangling alliances with none.” Both Washington and Hamilton agreed; they just stated it differently. It is worth quoting Washington’s Farewell Address at length:

Observe good faith and justice towards all Nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all. Religion and morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be that good policy does not equally enjoin it? . . . In the execution of such a plan nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular Nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded; and that in place of them just and amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation, which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. . . . A passionate attachment of one Nation for another produces a variety of evils. . . . The Great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign Nations is in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connections as possible. . . . Taking care always to keep ourselves, by suitable establishments, on a respectably defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.

As is made clear from the quote above, the Founders were not “isolationists,” in any sense of the word, but wanted peaceful, harmonious, and commercial relations with all nations. They wisely advised that we treat all nations equally, eschewing both “habitual hatred” and “habitual fondness” for any nation, or as the Declaration of Independence justly sums up, treat foreign nations as “enemies in war, in peace friends.”